Knowing how fights are started and controlled is an invaluable but often poorly understood part of RoN’s combat.

Stemming from the above you end up with a broad category of units that can be considered the “backbone” of an army because they must exist for an army to be able to negotiate control of fights.

Note: To keep it simple, we’ll be covering just fights with two sides (e.g. a 1v1), but the same basic principles can scale up to fights with any number of players and sides involved.

Fight Control

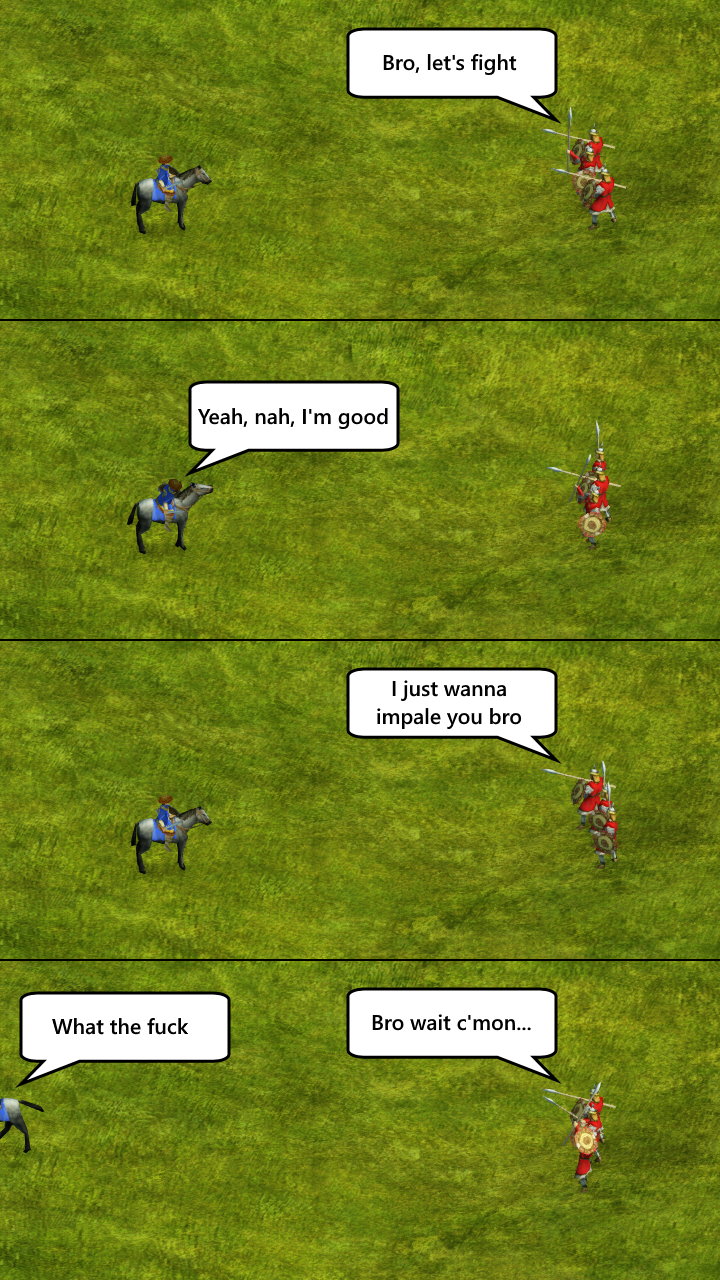

Initiating fights is much like an ongoing negotiation between the sides involved.

The attacker asks to fight, and the defender can either say yes (and they begin fighting), or say no (and the defender takes a step back). This can happen repeatedly, and ends with either a full-on fight breaking out, or the attacker giving up and leaving, or the defender dying during their retreat.

For a fight to break out, there has to first be a reason to fight. If there’s no reason to fight, the negotiation will automatically fail. The attacker presents themselves and announces that they wish to engage in a squabble. The defender looks around at the empty space around them which has no strategic value, shrugs, and walks away.1

However, sometimes a defender doesn’t want to fight but the attacker can force combat anyway. I describe this concept as “control”. This mostly happens because of two unit stats:

Superior speed can let you engage a unit even if it doesn’t want to fight since “running away” no longer means “avoiding damage”. This will either give you free damage on a unit that continues to flee, or force a unit to stand its ground and fight (even if it would lose). For the fight to actually turn out well, this has to be combined with actual combat prowess though – for example, Light Cavalry will almost never want to make use of their superior speed to force fights against Heavy Infantry, but would be happy to do so against Light Infantry.

Superior range can let you scuffle with opponents from outside of their effective range, forcing them to either concede ground (and probably get shot in the back a few times while they leave), or make a charge to try to kill you (or make you back off). Note that range has to be combined with a basic level of speed and/or combat prowess in order to avoid an immediately lethal charge by opponents. Catapults have superior range but are too slow to run away and can’t win a head-to-head fight. Contrast this with British Longbowmen, who have almost as much range but can reposition easily and also fight more effectively if forced to.

In theory, raw power (high damage and durability) can also overcome poor range and speed to provide an unconventional type of control, but there are no examples of this in Rise of Nations unless you publish a new version of the game where a major bug causes all units deal/receive the wrong amount of damage – in which case elephants can fit into this category (especially War Elephants).

Sometimes high raw power can be combined with good-but-not-exceptional speed or range (or both) as a way to acquire control. Heavy Cavalry sort of accomplish this, although their speed is only slightly above-average so I would certainly describe their control as good-but-not-great. Their control is somewhat weaker than other units with “true” control from genuinely standout speed or range.

Offensive and defensive control

So far I’ve been using “control” to more specifically mean “offensive control”: units with this property can basically bully other units.

However, there’s also the weaker “defensive control”, which means that a unit can’t be bullied (making it good defensively), but lacks the ability to bully other units. Heavy Cavalry have great defensive control but only average offensive control.

Put another way: if two units meet in an open field, and the first is instructed to kill the second:

- A unit with strong offensive control in the matchup is able to kill the other unit, regardless of whether that other unit chooses to fight or chooses to run.

- A unit with strong defensive control in the matchup is only able to kill the other unit if that other unit decides to stand and fight, but not if it runs away.

In bad matchups a unit will have neither type of control, such as when countered (e.g. Light Infantry gets murdered by Light Cavalry).

“Control” is just an abstraction of a unit’s performance while in combat, combined with how its range/speed compares to other units. Good combat performance with worse range/speed typically leads to good defensive control (it can defend an area effectively because it can’t be pushed around) but poor offensive control (it can’t take control of a defended enemy area effectively because it can’t push the enemy units around).

We’ll go over this a bit more with examples below.

Control Throughout the Ages

If you examine how each of the various land units fight pre-Industrial, you end up with this list of units that can control fights offensively:

| Control via speed | Control via range | Control via power+speed | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age I | Bowmen | ||

| Age II (Mil 1) | Light Horse* | Bowmen | |

| Age II (Mil 2) | Light Horse (lesser) | Archers | Cataphract |

| Age III | Light Cavalry (lesser) | Crossbowmen (etc) | Knight |

| Age IV | Elite Light Cavalry (lesser) | Arquebusiers | Heavy Knight |

| Age V | Hussar (situational) | Musketeers | Cuirassier (situational) |

* This is mostly relevant in nomad (tech: very expensive and slow) where this phase of the game can last more than just a minute or two.

Generally speaking, units that have good control have many good unit matchups and few bad unit matchups. The classic example of this dynamic is how Heavy Cavalry beats everything except Heavy Infantry, yet HI can never assert offensive control over HC because they’re both melee units but HC is the same speed (or faster). In other words, none of the standard units can control HC.

Age I

There are only three units2 and it’s a clear rock-paper-scissors matchup of unit counters. However, although Bowmen lose to Slingers in head-to-head combat, they’re still the unit with the by far the most control at this point in the game. They have similar speed but modestly better range than Slingers (so Slingers have no offensive control over them), but vastly outrange Hoplites and civilians, giving them strong control in those matchups.

Light Infantry apologisers will point out that Slingers also outrange their counter (Hoplites), and so Slingers should also be considered to have good overall control, just like Bowmen. The missing piece of the puzzle here is attack animations. Bowmen have an average attack delay of ~0.86 seconds before releasing a projectile, but Slingers have an average attack delay of ~1.37 seconds. In practice this means that Slingers have to stand still for a long time in order to actually deal damage, greatly hampering their effectiveness in real combat.

In the end, Bowmen are the unit with the most control.

Age II (Mil 1)

Once horses are in the mix, Bowmen are no longer semi-immune to being controlled, and so have to learn to share the stage with the new equestrian overlords. Interestingly because Light Horses also beat Slingers (the only other Bowmen counter), Light Infantry are useful only briefly before basically being superseded by another unit with a similar cost that does much the same job but better.

| Attacker (left) / Defender (top) | Slingers | Hoplites | Bowmen | Light Horse |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slingers | - | Lose head-to-head, but not controlled | Defensive control only | Slaughtered |

| Hoplites | Defensive control only | - | Slaughtered | Defensive control only |

| Bowmen | Lose head-to-head, but not controlled | Slaughter | - | Slaughtered |

| Light Horse | Slaughter | Unable to beat, but not controlled | Slaughter | - |

In isolation, this would make it look like Light Horses wouldn’t need to share the stage – they have two strong matchups and one matchup where they lose but don’t get controlled.

However, when multiple units are combined the reason is apparent. If Hoplites guard Bowmen, then the new combined infantry force actually gains offensive control over Light Horses. It’s now able to deal damage from afar (Bowmen) and also not lose in head-to-head combat (Hoplites). This is an extreme example of armies being more than the sum of their parts.

The counter to that combination would naturally be to add Bowmen of your own alongside the Light Horses, in which case the new duo beats the old duo. Although Bowmen on both sides are able to control the melee unit in the opposing force, Hoplites are far more vulnerable to Bowmen than Light Horses are. They take more damage per hit, are much less capable of dodging the arrows due to their lower speed, and are liable to lose DPS output if damaged because they’re an infantry squad, rather than a single unit.3

So you end up in a situation where the Hoplites need to retreat against the enemy Bowmen, effectively forcing their own Bowmen to retreat as well, as the fast-moving Light Horse will cut them up if they don’t move alongside the Hoplites.

Age II (Mil 2)

Horse Archers are largely not relevant for direct combat, since they lose head-to-heads against everything except Heavy Infantry and civilians – so we’re going to ignore them here.

Heavy Cavalry mostly fulfills the same overall role as Light Cavalry in combat, trading some of the latter’s speed for much higher durability. Of note, Heavy Cavalry also have strong defensive control over Light Cavalry, influencing the dynamics of which units are strongest at this tech level.4

This pushes LC into a position of reduced overall control, now having as many bad matchups as it does good ones – and it’s typically outperformed by HC even in those good matchups. However, its speed is a redeeming feature that allows it to never be truly controlled by the units that counter it, and that same speed allows for rapid combat maneuvers which no other unit can match.

Age III

In Medieval, nations with access to crossbows (rather than bow-based units) gain some extra control due to the hidden power that comes from high projectile speeds and fast, consistent attack animations.

Knights also gain 20% attack speed when upgraded from the earlier Cataphracts, further increasing the havoc they can wreak if they reach an undefended backline.

However, neither change is enough to fundamentally change which units have control, and the overall dynamics are fairly similar to what they were in Age II.

Age IV

Gunpowder Infantry (Arquebusiers) all but completely supercede Foot Archers, having the same range and nearly the same performance against Heavy Infantry, but with a roughly 50% durability increase, and improved matchups against melee cavalry (they still lose, but deal more damage).

Gunpowder Infantry also completely dunk on Foot Archers in head-to-head combat, cementing their ascension into the new dominant ranged unit of the time.

Control dynamics are otherwise largely the same as the previous two ages.

Age V

Conventional wisdom about dynamics in this age is that they’re similar to Age IV, with the addition of guns for Heavy Infantry making those units stronger but not really changing control. I held this position for a long time too, but recently changed my mind while running balance tests.

In my opinion, the same Hoplites + Bowmen combination from Age II (Mil 1) is reborn here in a stronger form with the Musketeers + Fusiliers combination. In army-vs-army combat, it is extremely difficult to gain offensive control over an army that’s compromised primarily of a combination of these two units unless you either outnumber them or hyperspecialise (e.g. all Musketeers, which is extraordinarily vulnerable to melee cav as a counter).

Not only do Fusiliers do significantly more damage against melee cavalry than the previous Elite Pikemen, but their range and default formation position (behind, rather than in front of Gunpowder Infantry) makes it highly impractical to attempt engagements against only one of the two units in the duo.

Melee cavalry can still annihilate out-of-position Musketeers that stray from the Fusiliers, but a wise player will prevent most such opportunities by keeping the infantry duo in smart formations. The Fusiliers are still vulnerable to enemy Musksteers, but safely reaching them when they’re behind other Musketeers is essentially impossible.

(Because this is a comparatively novel idea about Age V combat dynamics in a game that’s just shy of two decades old, I’ve elaborated more about this in a separate article.)

Age VI and beyond

I won’t go over this period in detail, but land-based army compositions become a fucking mess.

Basically:

- Tanks have winning head-to-head matchups against every other unit (except HI), but also have equal or better range as every other unit.5

- HI are the only land-based counter to tanks, but are outranged by every other unit (including the tanks that they’re supposed to counter), making them one of the worst “good” matchups in the entire game. It’s equivalent to if Hoplites outranged Slingers, or if Cuirassiers had the range of Musketeers.

- The combination of the two above points means that tanks (particularly Light Tanks) have the strongest control of any unit at any point in the game.

- The redemption for late-game unit counters is air power, but that mostly only applies in VII/VIII, not in VI,6 leaving one age where rock-paper-scissors simply doesn’t function. 15 Light Tanks and 15 Riflemen (with +8 armor) beat 10 Light Tanks, 10 Anti-Tank Rifles, and 10 Riflemen (with +8 armor) – and it’s not even that close.7 It’s really bad gameplay.8

Control: The Backbone of Army Composition

Generally speaking, you want to make use of army compositions that have good control, and this tends to make individual units with strong control the backbone of army compositions.

Contrast the following two Age III armies:

Army 1:

– 8x Knights

– 8x Crossbowmen

– 8x Pikemen

– 1x General (+4 armor)

Army 2:

– 12x Light Cavalry

– 12x Elite Javelineers

– 12x Pikemen

– 1x General (+4 armor)

In a full-on brawl, Army 2 will usually win9 in a fight, largely because it simply has 50% more units. But it will rarely be able to fight on its preferred terms, as it lacks offensive control. Its Elite Javelineers have lower range, much worse attack animations, and much lower damage against armored units than Crossbowmen, while its Light Cavalry will struggle to participate in fights without being exposed to both of its counters.

In order to force a fight, Army 2 would need to be willing to immediately lose all of its LC just to keep the enemy force in place, after which point it still doesn’t have offensive control because it can no longer effectively threaten the opposing army’s Crossbowmen if all of its LC are dead. Army 1 could absolutely just kill the LC and then still leave.

However, if Army 2 was attacking a city defended by Army 1, then this wouldn’t be as a big of a deal. Army 1 would now have a reason to fight and so Army 2 wouldn’t need offensive control to take an engagement.

Using control on the field

When you have a control advantage over your opponent, you can use it to fight on your own terms. Here are a few examples.

As an attacker: If your control stems from range, use your ranged unit(s) to weaken your opponent prior to a full engagement. If your control stems from speed, engage decisively when the opportunity to do so is available.

If you don’t have good control against your opponent’s composition, you could choose to change your own army composition to improve it. Alternatively you can negate the control problem by sieging, or avoid it altogether by focusing more on raiding rather than army-vs-army combat.

As a defender: If your opponent’s army does not have control of your army, any engagement that happens is voluntary on your side. If you don’t want the fight, just walk away. I often see less experienced players opting into bad fights where their opponent doesn’t actually have control, and of course when you take bad fights you tend to lose them. Assess your army vs their army, and avoid bad fights where feasible.

If you’re getting sieged but actually have better control, you can actually temporarily control the engagement before the sieged structure (usually a city) falls. For example, you can use range-based control to pick off some units at the edge of the fight, or maybe use speed-based control to cut off enemy reinforcements while producing your own. Of course, sooner or later the siege will force you to make a decision about whether you want to commit to a fight or instead retreat, but by controlling the engagement prior to that moment, you might be strong enough to be able to win the fight by then.

- Obviously this doesn’t work if the defender is a fight-crazed maniac.

- (plus Citizens)

- Killing sub-units lowers the overall DPS of the unit, which you can’t do when then there are no sub-units, such as in the case of cavalry.

- If you prefer to play the bugged version of the game without patching the damage bug, Heavy Cavalry still counter Light Cavalry, but the effect is less pronounced.

- (excluding artillery)

- Partly because Biplanes have low fuel and low turn speed, partly because Helicopters (which counter tanks) don’t exist yet.

- Microing literally every unit (using pause) to target what it counters makes it closer but it’s still a win for the 15/15 army and there are no players that can replicate individual real time management of 30 individual units.

- If “real life accuracy” is your argument for why this isn’t bad gameplay, then you should be campaigning for the tanks to be able to hit targets from across the map, and for each hit to kill units in 1-2 shots. Very few parts of RoN are truly accurate to reality, because it would be bad gameplay.

- The specific outcome depends heavily on how each side micros its units. With no specific micro (just attack moving into the enemy force), Army 2 reliably wins the engagement. Given sufficient micro, Army 1 can still win though, since it can dictate favorable terms for the fight by constantly kiting backwards.